When a theatre season is over, the work lives on in forms of documentation that are inevitably partial: video that captures action but can’t replicate the audience experience; writing that expresses particular perceived experience but can’t convey the whole; scripts; photos; memory. Even for the work’s creator, reflecting on past work must generally entail a lining-up of disparate fragments; a gleaning; and a resistance, perhaps, to the fragments and memories that have become most familiar.

A career, too, can be summed up in parts: the works, their relics, the collaborators, the dates and places. The story is chronological, seeming to tell itself; but for an independent artist, especially, the opportunity to glance backwards comes rarely.

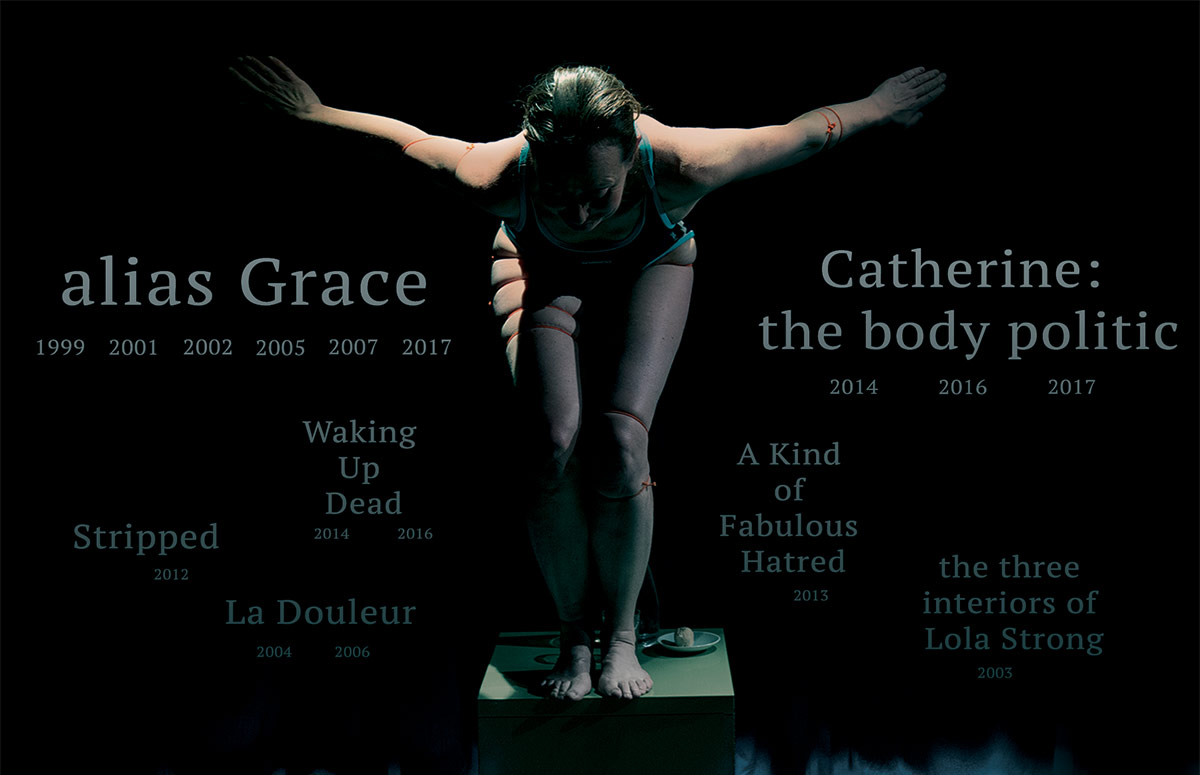

So for Caroline Lee, the re-mounting of her first solo piece, alias Grace (1999, 2001, 2002, 2005, 2007, 2017) – adapted from Margaret Atwood’s novel with director Laurence Strangio – and her most recent, Catherine: The Body Politic (2014, 2016, 2017), was a chance both for audiences to experience or re-experience these works, and for Lee to reflect on her output as an independent maker; in part by reinhabiting – not just remembering – these ‘first and last’ pieces. The following interview is part of a much longer reflection – on the ‘performing body’ and its lines of enquiry, its politics and its changes over time; and how the works sat ‘then’ and sit now amid theatre’s – and life’s – inevitable ephemerality.

UD: Firstly, why the title, Diving into the Unknown?

CL: Because, thinking back to the very first season of alias Grace at La Mama, 18 years ago, I still remember waiting behind the set as the audience came in, by myself, hearing their voices and their excitement and their noise – their presence – and it was very frightening. Suddenly I realised, in a way that I hadn’t until that point, that I was going out there alone, to do this act of creation all by myself…and that felt like a very unknown space. I really didn’t know what was going to happen out there. And the notion of leaping into the unknown becomes diving, because of Catherine: the body politic; [in particular] the scene of the schoolgirl, Kat, braving the swimming pool, braving her peers, and diving into the water. Diving into freedom, diving into herself.

How do you think alias Grace and Catherine: the body politic reflect the themes of your work of the past two decades?

First, alias Grace is a significant work in that it foregrounds my familiarity and deep love of text, of words, of literature, and of what words can do – what they can evoke in the imaginations of the viewers – and how much people still love to watch and hear a really good story. This interest in text…was then played out most particularly in subsequent solo works, La Douleur and Stripped, but also came into play in other works I’ve done, like Black at the Malthouse, which was a live installation work directed and created by Anna Tregloan.

In the remount of alias Grace this time, I was really struck by how physical the work is, how deeply embodied. I know that my physicality is very important in so many ways – e.g., the shoes a character wears are always crucial to me because they so deeply affect the way the body moves in space – but I suppose that I have always been so embedded in that, knowing that from inside, that I’ve not really seen it so much from outside the work.

Catherine: the body politic develops and extends themes which have been cropping up in my work for many years, and also my ongoing interest in the way stories are told, their structure and form. The first major solo piece I wrote myself was the three interiors of Lola Strong (fortyfivedownstairs, 2003). It was about a fictional architect, Lola Strong…and I was investigating the relationship between interior and exterior spaces in the psyche, and how those interior and exterior spaces shape identity, particularly Australian identity. There was also an exploration of a mother/daughter relationship… I think that it’s pretty clear that the themes of Catherine: the body politic are sitting in this same territory. With Catherine: the body politic I was very influenced by visual art, and I wanted to extend the fragmentation of form to see how far it could go. In terms of form, I was making a work of abstract art… [Everything is] working together in subtle, interconnecting ways to make a whole which is larger and more coherent than the sum of its parts, but this coherence and connection is not obvious or literal.

Regarding the physicality you became so aware of in alias Grace: what are the ideas or principles behind this physicality in your work? Have these ideas changed over time?

The three years of Laban training that I did while at drama school made me understand that character is created not just through ideas, drives, expectations, history, objectives, and words but also through the body – that the inner world is reflected and revealed in the body and the way in which the body works in space… I think that these ideas have become more firmly held, if anything, as I’ve become older. I [also] think I’ve become more physically confident and expressive…even more interested, as Catherine reveals, in what the body can hold and express and tell and show in a work of theatre; interested in what the body does which is in harmony to what is spoken, and what the body does which is in counterpoint to the text.

As characters, do you think Grace and the ‘Catherines’ have things in common?

I definitely think there is a connection between Grace and some of the Catherines around the ideas of ‘being seen’; and also what it is, and how important it is, for many women to speak, to be heard. There is a line that Grace says: “As for what I was named after, it might have been the hymn. I hope I was named after it. I would like to see. Or be seen.” And Cathy, one of the Catherines, says, “I wanted to speak”. Also, the academic, Kathryn, in many ways provides a framework through which to view the whole work, Catherine: the body politic, and her text is very much about the right to speak and be heard…as well as being seen.

In returning to alias Grace now, nearly two decades after its first season, how has your relationship to the work changed?

One of the things which we really noticed in alias Grace was that the framing of the work shifted. In the novel, the older Grace appears only at the end…you have a sense, at times, of a distance from the events, and some kind of ‘critical eye’, but this could just as easily be Grace’s own shift in perspective as she lives her life. However, because I am now embodied permanently in the story as an older Grace, in the stage version this time the sense of the retrospective telling of the story was unavoidable, and a much more constant presence in the work.

Also, between Laurence and I – but also, in particular, with the lighting designer, Bronwyn Pringle – we had often had a post-show moment of assessing whether on any particular night Grace was guilty or not; and this would change according to tiny shifts in my performance, or the audience reactions. Sometimes they were utterly swept along by her youth and innocence and vulnerability; other times, very cynical and critical of her. As the various seasons went on, I had to be careful to hold the balance in the work, so that both views were possible. We noticed that in this season, as an older, more knowing person, I had to work harder to keep the possibility of her innocence and lack of knowledge alive and present.

You’ve spoken previously about having a strong sense of your own ‘line of enquiry’ as a creator. How would you summarise that ‘line of inquiry’?

I would say that my line of enquiry has been a fascination with Australia; in particular, with how the landscape has affected our identity and development as a nation and as individuals. I am also a strong advocate for an Australian voice within culture, for telling our own story, as it evolves, rather than getting swallowed within various other dominant cultures.

Another strong interest has been in the position of women within Australian culture – all facets of it. My mother was an unusual woman in that she was a botanist, worked in the Forestry Commission, then at universities, married a man ten years younger than herself, had a career, and had one child at the age of 40. Her mother, and other women in my family circle, were strong, independent women – other academics, many professionals, a lot of unmarried women – and I suppose that this awakened a curiosity and interest in me about other ways of being a woman, and how and what it was to be a woman, both in the past and in the present.

In your portrayal of both Grace and the Catherines, there are many moments of parody or irony that come across as both funny and sympathetic. What role does humour play in your work?

[Humour is] such a clever mechanism to elicit understanding – it’s like a subtle parallel channel through which understanding and interest and desire can be awakened. It is real and brutal and truthful and present and alive; and because it is necessarily connected to the actual moment in which it happens, it keeps both performer and audience alive in, and to, that present moment.

Do you think of your body of work as ‘political’?

Yes, although I’ve never been very interested in overtly political theatre. Theatre, however, which has a very solid engagement with politics and then builds around this, can be deeply engaging and inspiring. Fragmentation helps; I think the old writer’s dictum of ‘show-not-tell’ helps. Utilising all of the tools of theatre – body, light, sound, costume – also helps to make an idea rich and layered rather than mono-dimensional; for an idea to stay ‘open’ to provoke curiosity and engagement rather than shutting it down.

alias Grace is political because it’s very firmly set within a framework of class and gender. And I think some of the Catherines are more overtly political than others, but the framework is political because it’s about gender and also to some extent about outsiders – regional, social, class or otherwise.

As for my career – well I’m sure that my politics have absolutely had an impact – on the work that I’ve made, been cast in, and the people and companies with whom I have worked. There’s nothing more frightening – or perhaps just irritating – to a certain sort of white, heterosexual director than a woman who thinks and is not frightened to speak. I used to worry about that, but I don’t any more so much.

Do you think alias Grace and Catherine have accrued different meanings over time, or impact differently now?

Sadly, the feminist issues in alias Grace – of the agency of women, of being treated properly and equally – are still as important and relevant as they were when we first mounted the play in 1999…and indeed, in this era when neo-conservative attitudes are taking hold, possibly even more pressing. I think also that this time round – probably as a result of Australia’s own increasingly harsh and punitive and ungenerous attitudes to immigrants and refugees – I was much more aware of the racial prejudice which had been applied to the historical Grace Marks on account of her being an Irish immigrant in Canada, and thus, at that point in history, much maligned and mistreated simply for her nationality.

Another unexpected thing which struck me about alias Grace, this time, was how the theatrical landscape has changed since we first made it. Most particularly, there has been the widespread adoption and exploration of various aspects of ‘post-dramatic theatre’ (and I suppose that you could say that Catherine: the body politic is a product of this tendency in theatre, although I was not really conscious of that as I made it) such that work with a strong story, a clear narrative thrust, is much more rare than when we first made the work; and certainly some audience members this time round were surprised at how strongly they were gripped by, and enjoyed being told, a really good story.

At this point in your career, how do you think about ‘success and failure’, or even the ‘shattering’ of dreams or beliefs that you mention in the program notes for Catherine?

For me, success means many things. Most importantly it means feedback, in the moment, on stage –either silence, utter spellbound silence, or laughter or sighs, moans, little responses that you hear from on stage. Or people writing to me, through my website or email, or even by letter, to express gratitude, pleasure and encouragement. Or staying after the show to speak to me about the work, or coming up to me in the street and wanting to talk about what they’ve seen in the performance. It is that something has been communicated, transmitted: a thought, an idea, a vision, a concept. That is what’s most indicative of success for me…something given and received.

I have had some spectacular failures. I don’t think it’s really possible to escape one’s flaws… I think it’s possible to investigate them, to know them, to become deeply acquainted with them, and in that way perhaps let them rest, sidestep them, be freer from them…but not leave them behind totally.

Actually, I think the shattering of dreams can happen at any time. I suppose I am interested in that because I’m interested in what can actually change us – and these moments of shattering are moments of change, of transformation. I don’t know that this theme has become more important over time, but I certainly think that as I’ve become older I can be more measured and perhaps less self-destructive, more curious and more thoughtful about my failures, both internal and external…about the notion of failure itself – although not always.

You mounted Catherine as an unpaid project after more than two decades of professional work…why? Is this, too, a kind of politics?

There’s been a few articles in the media about how doing theatre, because it requires so much dedication and time, and involves such financial insecurity, is really only available to the middle class. It seems to me there is some truth to this. I have endured long stretches of very low income, and worked for many many years in relatively crappy causal jobs. And, I have no children. I do think that I was able to withstand the low income and the difficulty of those long years with a lot of unpaid or low-paid work because I have the security of my family behind me, and also no dependents.

If you are unpaid, you can potentially be free, creatively. Of course, this is not necessarily so. So much conspires to bind us. Poverty is a bind. Even freedom itself can be a bind. But for me, yes, I am driven to create, write, make; to communicate ideas about the world I live in, and if I have to do this part-time while some other activity provides me with the means to survive, so be it. I suppose it’s a political act. It’s certainly defiant.

It’s wonderful to be able to see these works again in a retrospective season, and a pity such seasons are so rare. But are there positives, too, in theatre’s ephemeral nature?

Unless you have something like five cameras and proper sound, live performance can’t really be captured on film. What is lost is the elusive, living, breathing, moment-to-moment exchange between performers and audience; the particular social and cultural moment, shared knowledge, shared experience between performers and audience.

[But ephemerality] is the nature of life, as well as theatre. And so, it keeps work alive, and life is the essence.